For a History Lesson and reminder of the role Disabled people have played in activism, I singled out a few instances, but there’s hundreds of thousands throughout America’s history. Many of the privileges and rights people have had are due partly to the fight of our disabled ancestors.

(Much of this post references the following books: A Disabled History of the United States by Kim Nielsen, White Rage by Carol Anderson, A Queer History of the United States by Michael Bronski, and An Indigenous People’s History of United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. Any other references are linked in the post).

A Bit of History, starting in 1800s as an Intro

Through the 1860s through 1940s, the Ugly Laws as they came to be called dominated many of the state and federal laws. These laws made it a crime for a person with a “physical or mental deformity” to be out in public places. Since a large percentage of Civil Wars veterans came home disabled, many of these laws targeted them.

As an example of an Ugly Law, San Francisco in 1867 banned ““any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object” from the “streets, highways,thoroughfares or public places of the city.” Other cities such as Chicago and Portland and many others soon followed suit.

These city officials claimed distinctions based on class, and furthered the demonization of disabled people with anti-begging ordinances. Thus locking out of public sphere and out of jobs many poor disabled people.

However, despite these ugly laws, the public grew fascinated with what they deemed “deviant bodies” and as early as 1840s, traveling “freak shows” in vaudeville, P.T. Barnum’s Museum in New York, circuses, county fairs, and World fairs. Disabled people were put on display based on “physical and mental deformities.” For some disabled people, this was the only way to survive.

Institutionalization and demonizing of “Deviant Bodies”and “antisocial behaviors”

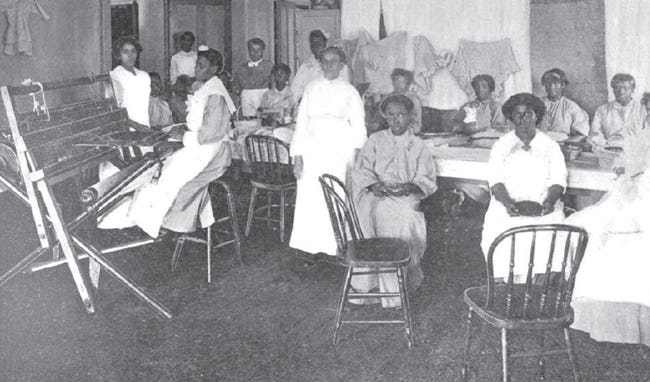

After Civil war, insane asylums began to increase as well, and patients were segregated based on gender, race, and “physical and mental deformities.” These places were often deadly due to poor medical hygiene and care. Experiments were also conducted on patients. For example, Dr. Julius Wagner-Jauregg would without consent from the patient purposely inject them with malaria to ‘cure syphilis’ and many died from malaria.

The diagnoses for admission ranged from epilepsy to religious excitement to disease of the brain to fatigue to hysteria.

Those admitted included war veterans, women, Indigenous people, Black people, and anyone the medical establishment deemed ‘physically or mentally deformed.’ They’d often trapped there, with their right to freedom rescinded. It was incredibly hard to leave the insane asylum, as even arguing for freedom could be deemed a ‘mental deformity.’

For Black patients, medical institutions relied on harmful racial theories, which resulted in even worse care than white patients, increasing the malnourishment and mortality rates.

Historian Jim Downs wrote: “freedom depended upon one’s ability and potential to work… Scores of disabled slaves remained enslaved for decades.”

If not trapped in their prior enslavement, they often ended up incarcerated within insane asylums.

The intersection of class, gender, race, and (dis)ability resulted in the loss of freedom for many within asylums.

Between the increase in insane asylums, ugly laws, and anti-begging laws, many disabled people found it near impossible to exist in public at all. Who was labeled insane or “deformed” shifted and changed to include more people of specific demographics, especially those targeted by city, state, or federal governments. The Medical establishment played a large role in such approaches to anyone that was deemed “deviant” by authorities.

These laws were enforced brutally, but also met with resistance from disabled people of all races and gender. However, many of these ugly laws were not fully repeated in may states until the 1970s and 80s, and in some cities, they were never fully repealed, simply not enforced due to federal anti-discrimination laws.

Repealing the Ugly laws did not happen on a whim. It involved decades of intense protests, sit-ins, and coordinated sets of strikes by disabled union members and their non-disabled union allies, which grew outward from there. Since anyone of any race, gender, orientation, and citizenship status could become or be disabled, the fight involved people from many disparate and decentralized groups.

So with that introduction, let’s take a look at a few crucial examples that had a large role on the civil rights struggles.

Disabled Miners and Widows and the Mining Strikes of 1970s

In West Virginia 1968, seventy-eight miners died in a mine explosion, which shocked the country and put a spotlight on mining dangers. Regional doctors began to fight back against the mining companies’ long medical coverup and denial of black lung disease, and brought that to the union halls. About this time, “Tony” Boyle gained control of United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), and began cutting the pensions of Disabled mine workers.

In 1969, Joseph Yablonski ran against a corrupt “Tony” Boyle to end corruption within the UMWA. However, they were assassinated by Boyle, per the courts investigations into Yablonski and his wife’s death.

Angered, miners founded Miners for Democracy and together with Disabled Miners and Widows and the Black Lung Association, they led the fight to reform the UMWA.

Robert Payne and other Disabled miners in the 1970s started a five-week strike, where they compelled non-disabled miners to join them until over twenty-five thousand workers adhered to the picket lines. These disabled miners led the charge in reforming the UMWA union, which included strikes and lawsuits to push for regulations to make mining safer and for disabled miners to received their promised pensions. The abled-bodied miners understood they risked becoming disabled themselves via injury or daily intake of coal dust.

One crucial point is that there was no one leader for the wildcat strikes that started in 1970 and concluded in 1978. The movement stayed decentralized as the rank and file conducted their strikes from West Virginia to Illinois. This culminated in 1977/78 with one of the longest running strikes in labor history.

Solidarity across class, race, gender

Like prior Disabled activists in the early 1900s, Payne and the members of Disabled Miners and Widows proclaimed themselves worthy citizens. By using terms such as “rights” and “discrimination” the borrowed from earlier anti-war and racial freedom movements.

This fight grew outward from the miners as more activists, advocacy organizations, and ordinary citizens began to put pressure on the government to made disability a protected class. This fight intersected not just disability but also class, race, and gender.

In 1973, one notable activist, Clara Clow, fought for accessible public spaces in her town of Frederick, Maryland. Her husband helped organize the Disabled Citizens of Frederick County United.

“Our main focus is architectural and attitudinal barriers,” Clow told a reporter in August 1990. “In the beginning people really did think we were outrageous. It’s been kind of a long fight. I guess I’m an activist. I think it’s just caring.”

Much of the fights grew outward until pressure from disabled activists and their allies pushed for the American Disability Act to pass. There’s a lot of crucial justice work and solidarity that went into that century long fight, so I recommend reading up on it.

For now, I’ll focus on one of the important precursors, a fight Disabled activists today are having to face yet again.

Rehabilitation Act and Section 504

In 1972, Congress drafted the Rehabilitation Act, which was driven largely by the needs of Vietnam veterans. However, this act drew the gaze of the civil rights activists largely due to Section 504.

In Section 504, it stated that people with disabilities should not be “be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

The bill was first vetoed by Nixon in 1972, however, activists across the country from various disability advocacy groups and many student groups testified before state legislatures and Congress to push for the elimination of architectural, educational, bureaucratic, and other barriers. They argued heavily for elimination of these barriers and for the ability to be considered for jobs.

Despite Nixon vetoing the Rehab Act a second time, it passed in September 1973. Its section 504 gave disabled people legal and cultural frameworks to gain access to the parts of society they’d been denied prior.

However, these laws were not enforced. Through the lawsuit Cherry v. Matthews, activists pushed for enforcement regulations, and in July 1976 a federal judge ordered the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) to develop regulations.

With the continued federal failure to enforce Section 504, Disability activists staged demonstrations in Washington D.C. and in each of the ten HEW offices across the country. This sit in lasted twenty-five days. Judy Heumann helped lead one of the largest sit-ins of federal offices.

“Oh deep in my heart, I do believe that we shall overcome today,” protesters sang at the sit-ins.

These protests gathered allies from local and national labor unions who joined protestors and wrote statements of support.

When phone lines were cut, the Butterfly Brigade, who were a group of gay men who patrolled streets to stop antigay violence, smuggled in walkie talkies.

The Black Panthers provided one hot meal a day, and Chicano activists brought food regularly.

Chuck Jackson, who was part of the Black Panthers, joined the protest by provided attendant-care services for Disabled Black Panthers in the sit-ins and other protest members.

Increasing media attention brought the focus of the nation. Images and video of disabled people crawling up the steps to reach the sit-in were heavily publicized.

Four weeks into the occupation, HEW secretary Joseph Califano signed the enforcement regulations, thus ensuring all programs receiving federal funding could not discrimination based on disability.

The Fight for our rights is about access for all

In A Disability History of the United States, Kim Nielsen writes:

“Movement participants argued that disability was not simply a medical, biologically based condition. Indeed, the movement sometimes directly challenged medical authority to define “disability.” Using the work of activists and intellectual theorists such as Erving Goffman, Jacobus tenBroek, and Irving Kenneth Zola, advocates argued that disability is a social condition of discrimination and unmerited stigma, which needlessly harms and restricts thelives of those with disabilities and results in economic disparities, social isolation, and oppression.

Just as the civil rights movement critiqued hierarchy based on racial differences, and just as the feminist movement critiqued hierarchy based on sex and gender differences, the disability rights movement critiqued hierarchy based on the physical, sensory, and mental differences of disability.”

Part of that movement involved independent-living and deinstutitionalization of disabled people. In this vein, the disability justice movement slips into the abolition movement neatly. As both movements seek to end the imprisonment and non-consensual institutionalization of people the state deems ‘less than’ or ‘problematic’ or ‘too violent.’

Disability Justice developed the model of ‘spaces’ to help explain accessibility. Starting with architectural (physical) space, transportation space, and sensory space, various Disabled theorists and activists expanded upon these to better explain the barriers they faced. Other spaces include digital space, media space, information space, community space, justice space.

The ‘spaces’ model depicts the multi-layers of access (or lack thereof) which impact disabled people (of any race, gender, orientation, citizenship status, parent or non-parent). However, these ‘spaces’ also impacted abled-bodied people of other groups such as parents with kids, Black and Indigenous People of Color, LGBTQIA people, immigrants, and those at the intersection of all those identities.

The fight for accessibility and access never ended for disabled folks.

I’ll stop there for now. I really need folks to understand the crucial role disabled activists like myself play. And when we are abandoned and left for dead, that means all you currently abled-bodied folks are next, as any of you can become disabled at any time whether by virus, disease, accident, hereditary, born with it, traumatized, or proclaimed so by authorities.

Disability is the one marginalized group anyone can join at any time.

We are in this fight together. Listen to the activists of prior decades, see how the Disabled activists, Black Panther, union members, gay and trans folks all worked together to lay our activist foundation.

“Until all of us are free, none of us are.” Please do not forget us. Fight alongside us. Thanks for reading.

Thoughts?